It is ironic that just as the Ritz was opening as the epitome of the theater-going

experience, the movie industry was experiencing the somewhat painful changeover

from silent to sound pictures. When the Ritz eventually got a new manager

in the personage of A. H. Talbot of Chicago, Birmingham News

writer Dolly Dalrymple (whom we met in the Alabama Theatre discussion

at the beginning of this chapter) interviewed the new man with the company

and filed these comments:

It is ironic that just as the Ritz was opening as the epitome of the theater-going

experience, the movie industry was experiencing the somewhat painful changeover

from silent to sound pictures. When the Ritz eventually got a new manager

in the personage of A. H. Talbot of Chicago, Birmingham News

writer Dolly Dalrymple (whom we met in the Alabama Theatre discussion

at the beginning of this chapter) interviewed the new man with the company

and filed these comments:

"Especially during the last 10 years, when

moving pictures have been raised to the dignity almost of legitimate performances,

and practically all of the great actors of the legitimate stage have succumbed

to the fascination of the 'talkies,' has this business or vocation taken

on new life and new phases."

Mr. Talbot then chimed in with his views on how this changing business

of entertainment would continue to evolve: "Of

course the talkies today are still in the infant stage and the end of them,

well, no one can tell. One thing is certain and sure though, and that is

they have come to stay. Television is the next link in the chain

... I believe television will eventually be used exactly like the radio.

People will sit in their own homes and hear and see the play without going

to the theater for this purpose." If it sounds as though

Mr. Talbot wasn't telling anyone anything they didn't already know, please

take into consideration that his remarks were published in the paper on

March 25, 1931. We're sure Mr. Talbot, with his keen foresight, must have

made a bundle in the entertainment business ... especially if he were smart

enough to get out of theaters and into television!

For whatever reason, during the Ritz's long Birmingham stay, it became

the theater of choice for testing out every new device or system the motion

picture industry tried in order to get people away from that television

menace Mr. Talbot had so eerily prophesied. Actually, even before that

happened the Ritz had undergone two major remodelings (1933 and 1940),

but neither of them compared to the assault on the building's history that

began in the late 1950s.

First there was Todd-AO. What's that, you ask? Todd-AO

was the trade name of a new motion picture process that doubled the size

of the image from 35mm to 70mm film, and also involved the latest in high

fidelity sound. It was named in honor (?) of producer Mike Todd,

who introduced the "better than TV" format in his feature Around the

World in 80 Days. Installation of the new, curved screen, and the multitudes

of audio speakers required to produce the hi-fi sound, decimated much of

whatever was left of the Ritz's original structure and appearance. However,

the theater spared no effort in proclaiming that it could now show such

Todd-AO epics as The Big Fisherman and Ben-Hur (all of a

sudden we're back where the Jefferson Theatre started!).

Most

amusing of all was the newspaper's remark that "Todd-AO

has been described by reviewers as a 'practical version of Cinerama,' which,

because of its tremendous installation and operational expense, has not

been profitable for theater exhibitors except in the largest cities." With

that established, wouldn't you know that the next major remodeling program

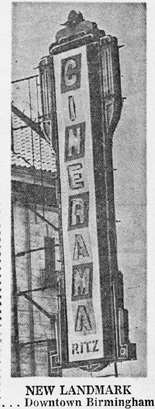

at the Ritz was to turn it into the state's first Cinerama theater? Most

amusing of all was the newspaper's remark that "Todd-AO

has been described by reviewers as a 'practical version of Cinerama,' which,

because of its tremendous installation and operational expense, has not

been profitable for theater exhibitors except in the largest cities." With

that established, wouldn't you know that the next major remodeling program

at the Ritz was to turn it into the state's first Cinerama theater?

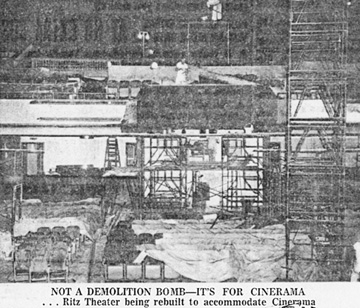

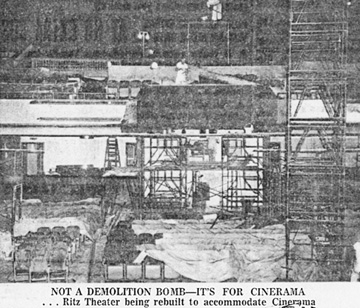

Yes, it's true: during the spring and early summer of 1962, the insides

of the Ritz were ripped out and rebuilt again, this time to provide the

multiple screens required by Cinerama, which had been trying to get people

out of the TV viewing habit and back into the theaters for almost ten years

by that time. The novelty might have worn off in the rest of the movie

industry, but Birmingham (and the Ritz) treated it as though it were the

greatest advancement in movies since Al Jolson. Buried down in all the

publicity was the offhanded remark that up to that point, the only movies

produced in the Cinerama format were travelogues. Thrilling as it might

have been to take a simulated roller coaster ride or view the beauty of

Florida's venerable Cypress Gardens in lifelike realism, moviegoers

wanted stories, and the Ritz had to wait almost six months before the first

(and some of the few) Cinerama movies with a plot were released.

The

conversion to Cinerama really destroyed the Ritz's small remaining amount

of historical value. The three screens took up the entire width of the

front of the theater, requiring that the chambers that once housed the

pipes of the $25,000 organ be unceremoniously closed off with cement blocks.

The number of seats dropped dramatically, from 1700 to 500. Even the Ritz's

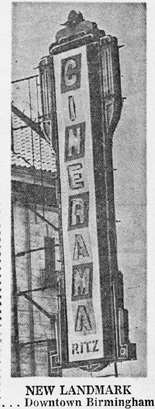

marquee received a Cinerama logo overlay, hiding the red and green neon

tubes that truly looked as if they belonged to another era. The

conversion to Cinerama really destroyed the Ritz's small remaining amount

of historical value. The three screens took up the entire width of the

front of the theater, requiring that the chambers that once housed the

pipes of the $25,000 organ be unceremoniously closed off with cement blocks.

The number of seats dropped dramatically, from 1700 to 500. Even the Ritz's

marquee received a Cinerama logo overlay, hiding the red and green neon

tubes that truly looked as if they belonged to another era.

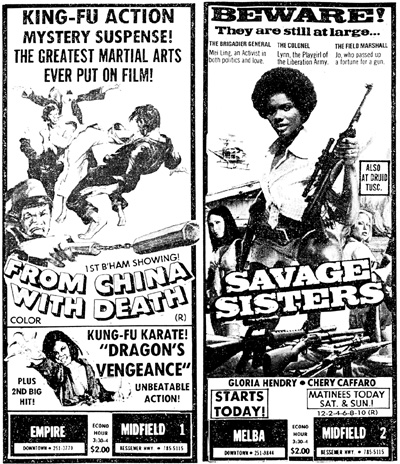

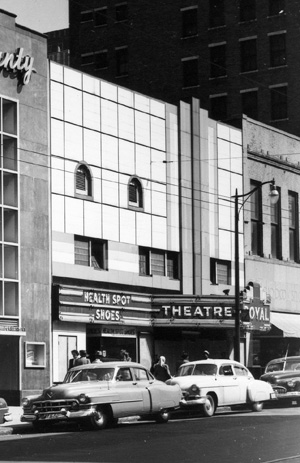

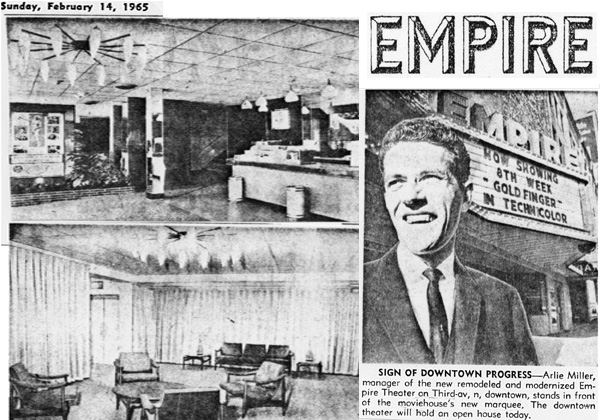

Ironically, within a couple of years Cinerama also belonged to another

era. By 1964 the Ritz was being remodeled (what, again?!), this time to

rid itself of Cinerama and get back to a more normal appearance. From that

point onward, things would go downhill for the Ritz. After years of steadily

declining attendance and interest, the old dinosaur coughed its last in

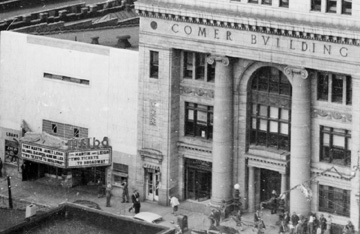

1977. In 1982, the Post-Herald newspaper sent reporter Terry

Horne down to Second Avenue to see if anything was left of the Ritz's

faded glory. "The green and red neon tubes are

now caked with dust, the white tiled front chipped and cracked,"

Horne wrote. "Still tacked to the glass-covered

boards are the coming attractions posters: a 1977 Richard Pryor movie,

a 1975 Clint Eastwood movie, and a personal appearance by 'Wildman Steve,'

a black X-rated comedian." (Somehow, it was good to know

that even in this perverted way, the Ritz was still holding on to its origin

as a vaudeville performance theater.)

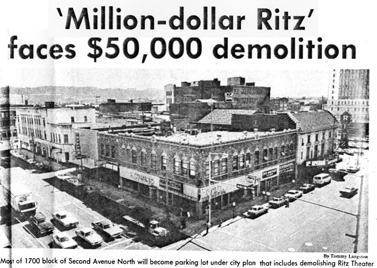

There was no movement to rescue the Ritz from the wrecking ball, as

had been done for the Alabama Theatre, because unlike the Alabama, there

was not enough left of the Ritz's original structure to classify it as

a historic building. Irony of ironies, all the remodeling it had seen to

keep it up to date over the years had destroyed the very thing that might

have preserved it. The theater and the entire block it occupied, including

the large Pasquale's Pizza restaurant on the corner, became a parking

lot in the fall of 1982. |

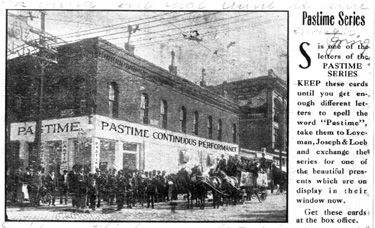

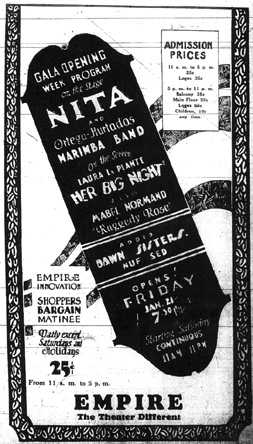

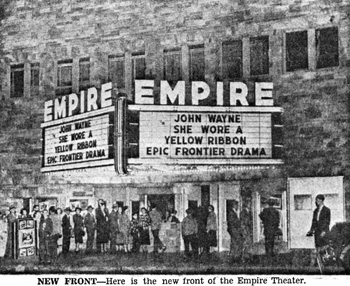

Of

those first few years, the Birmingham Historical Society reported,

"Eleven

movie houses first appeared in city directories of 1908 with such names

as Electric, Theatorium, Edisonia, Elite, Musetorium, Newsome, St. Nicholas,

Vaudette, Alamo and Marvel, but only two survived the following years."

The fact that these names are not the stuff of people's fond memories today

indicates that their influence -- indeed their very existence -- was somewhat

short-lived.

Of

those first few years, the Birmingham Historical Society reported,

"Eleven

movie houses first appeared in city directories of 1908 with such names

as Electric, Theatorium, Edisonia, Elite, Musetorium, Newsome, St. Nicholas,

Vaudette, Alamo and Marvel, but only two survived the following years."

The fact that these names are not the stuff of people's fond memories today

indicates that their influence -- indeed their very existence -- was somewhat

short-lived.

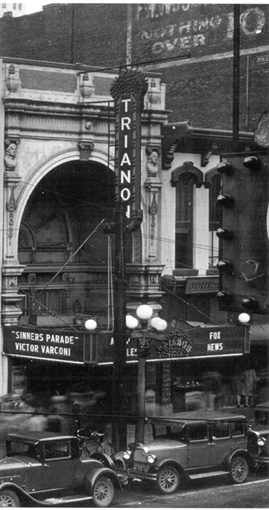

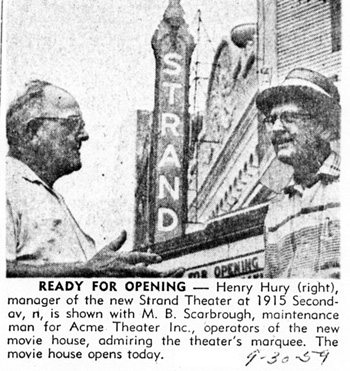

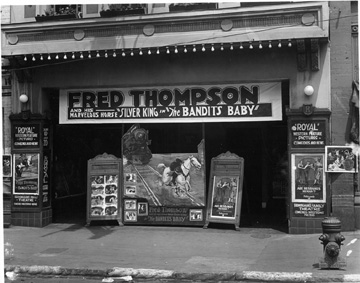

Whereas

the biggest names in vaudeville were appearing on stage at the Lyric, the

Bijou, and their kin, it was at the Strand that the newly-rising stars

of motion pictures could usually be found when passing through Birmingham.

Screen idol and future character actor Francis X. Bushman put in

an appearance at the Strand and was almost mobbed by his fans. Clara

Kimball Young made a scene that wasn't in the script when she arrived

and found the theater had no stage on which she could appear. The manager

hastily fashioned a platform out of parallel boards covered with flowers,

but it did little to mollify the actress's ruffled feathers.

Whereas

the biggest names in vaudeville were appearing on stage at the Lyric, the

Bijou, and their kin, it was at the Strand that the newly-rising stars

of motion pictures could usually be found when passing through Birmingham.

Screen idol and future character actor Francis X. Bushman put in

an appearance at the Strand and was almost mobbed by his fans. Clara

Kimball Young made a scene that wasn't in the script when she arrived

and found the theater had no stage on which she could appear. The manager

hastily fashioned a platform out of parallel boards covered with flowers,

but it did little to mollify the actress's ruffled feathers.

Meanwhile,

the new "million dollar" theater was given the name Ritz, and an

opening date of August 15, 1926. As was typical of the period, the silent

movie that was the opening night feature (More Pay, Less Work, starring

Mary

Brian and Buddy Rogers) took second row to the acts presented

on stage by the Keith-Orpheum vaudeville circuit. Star performers were

New York musicians and comedians Herman and Sammy Timberg; Sammy

would go on to make a bigger name for himself by writing the music for

the Betty Boop and Popeye cartoons for the Max Fleischer

animation studio during the 1930s.

Meanwhile,

the new "million dollar" theater was given the name Ritz, and an

opening date of August 15, 1926. As was typical of the period, the silent

movie that was the opening night feature (More Pay, Less Work, starring

Mary

Brian and Buddy Rogers) took second row to the acts presented

on stage by the Keith-Orpheum vaudeville circuit. Star performers were

New York musicians and comedians Herman and Sammy Timberg; Sammy

would go on to make a bigger name for himself by writing the music for

the Betty Boop and Popeye cartoons for the Max Fleischer

animation studio during the 1930s.

It is ironic that just as the Ritz was opening as the epitome of the theater-going

experience, the movie industry was experiencing the somewhat painful changeover

from silent to sound pictures. When the Ritz eventually got a new manager

in the personage of A. H. Talbot of Chicago, Birmingham News

writer Dolly Dalrymple (whom we met in the Alabama Theatre discussion

at the beginning of this chapter) interviewed the new man with the company

and filed these comments:

It is ironic that just as the Ritz was opening as the epitome of the theater-going

experience, the movie industry was experiencing the somewhat painful changeover

from silent to sound pictures. When the Ritz eventually got a new manager

in the personage of A. H. Talbot of Chicago, Birmingham News

writer Dolly Dalrymple (whom we met in the Alabama Theatre discussion

at the beginning of this chapter) interviewed the new man with the company

and filed these comments:

Most

amusing of all was the newspaper's remark that "Todd-AO

has been described by reviewers as a 'practical version of Cinerama,' which,

because of its tremendous installation and operational expense, has not

been profitable for theater exhibitors except in the largest cities." With

that established, wouldn't you know that the next major remodeling program

at the Ritz was to turn it into the state's first Cinerama theater?

Most

amusing of all was the newspaper's remark that "Todd-AO

has been described by reviewers as a 'practical version of Cinerama,' which,

because of its tremendous installation and operational expense, has not

been profitable for theater exhibitors except in the largest cities." With

that established, wouldn't you know that the next major remodeling program

at the Ritz was to turn it into the state's first Cinerama theater?

The

conversion to Cinerama really destroyed the Ritz's small remaining amount

of historical value. The three screens took up the entire width of the

front of the theater, requiring that the chambers that once housed the

pipes of the $25,000 organ be unceremoniously closed off with cement blocks.

The number of seats dropped dramatically, from 1700 to 500. Even the Ritz's

marquee received a Cinerama logo overlay, hiding the red and green neon

tubes that truly looked as if they belonged to another era.

The

conversion to Cinerama really destroyed the Ritz's small remaining amount

of historical value. The three screens took up the entire width of the

front of the theater, requiring that the chambers that once housed the

pipes of the $25,000 organ be unceremoniously closed off with cement blocks.

The number of seats dropped dramatically, from 1700 to 500. Even the Ritz's

marquee received a Cinerama logo overlay, hiding the red and green neon

tubes that truly looked as if they belonged to another era.

-----

-----