| That two-year discrepancy did not matter much in the long run, as the

Lyric would have shamed the earlier theaters no matter when it opened.

Built for the prestigious Keith vaudeville circuit, the Lyric sported

ornate balconies and wall ornamentation, and from its opening day featured

some of the biggest acts on the road. On opening night, the headliner was

cartoonist Rube Goldberg, and he was soon followed by another famous

gag man, Bud Fisher of the Mutt and Jeff comic strip.

Others who played at the Lyric during its first heyday were Will Rogers,

Sophie

Tucker, Jack Benny, and Fred Allen.

After

the arrival of the Lyric, the older vaudeville theaters began closing up

one by one. The repertory company from the Jefferson Theatre transferred

their allegiance to the Lyric, where they became known as the

Favorite

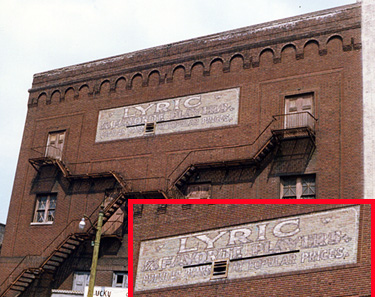

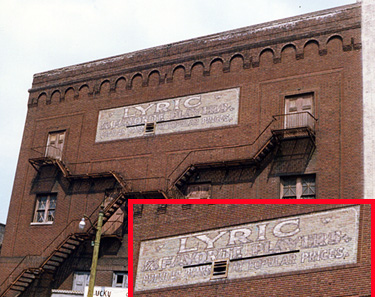

Players. (Look closely at the Eighteenth Street side of the Lyric building

even today, and you will see a fading sign painted on the brick, advertising

this troupe.) After

the arrival of the Lyric, the older vaudeville theaters began closing up

one by one. The repertory company from the Jefferson Theatre transferred

their allegiance to the Lyric, where they became known as the

Favorite

Players. (Look closely at the Eighteenth Street side of the Lyric building

even today, and you will see a fading sign painted on the brick, advertising

this troupe.)

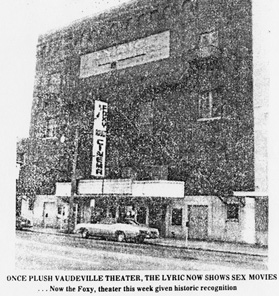

However, the combination of the dual arrival of the Great Depression

and the double sock of radio and the movies rang a sour note for the Lyric.

In late 1930 or early 1931, it closed its doors as a vaudeville theater,

and reopened in April 1932 strictly as a movie house. (Just to indicate

how show business was changing, the Keith vaudeville circuit had eventually

merged with the Orpheum circuit to become known as Keith-Orpheum.

This entity then hooked up with David Sarnoff, head of the NBC radio network,

to form a new movie studio known as Radio-Keith-Orpheum, or RKO

Radio Pictures. The movies were winning, there was no doubt of that.)

The Lyric survived on showing second-run features that had already played

the other downtown theaters until it was closed again, this time in either

1958 or 1960, depending upon what source one consults. In any case, it

looked like the end had come.

Around 1964 there was some talk of renovating the Lyric, but nothing

happened until 1973, when a couple of Jefferson State Junior College pals

(and old movie buffs), Dee Sloan and Robert Wharton, got

the bright idea to reopen the Lyric to show classic movies of bygone eras.

Rather than keeping the Lyric name, which had no doubt become tarnished

from its years as a second-rate showplace, Sloan and Wharton redubbed it

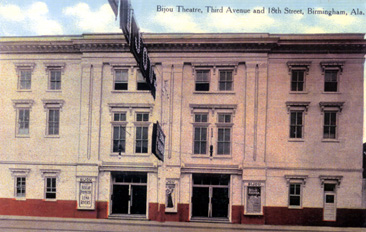

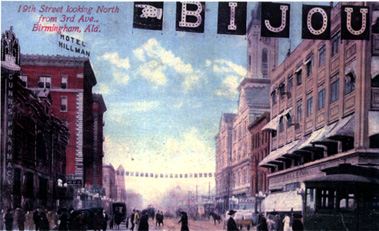

the Grand Bijou, and set about to show such cinema milestones as

The

Jazz Singer and classics starring W. C. Fields and the Marx

Brothers. While preparing the old theater to come back to life, the

new movie moguls discovered that underneath the main floor was an enormous

tank that would have been used for staging such vaudeville spectaculars

as Billy Rose's "Aquacade." although there was no evidence that

water acts of that type had ever appeared there. |

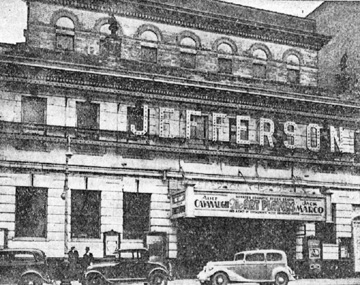

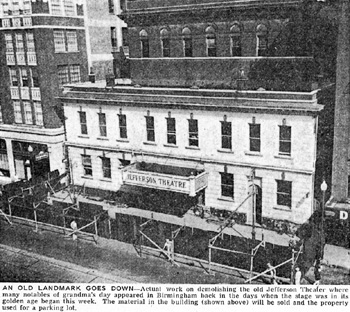

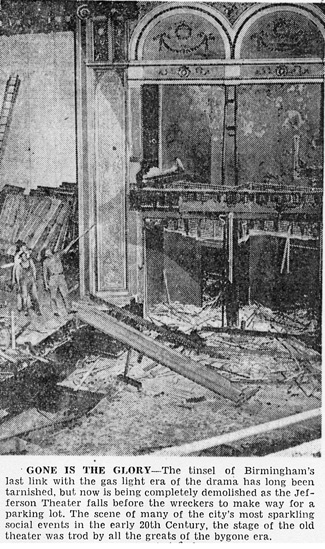

It is fortunate that over the years several people who actually witnessed

performances at the Jefferson recorded their memories for posterity. In

1960, stage hand Henry Holtam told the Birmingham News about

one of his most vivid recollections: "Ben-Hur

was the most spectacular show that ever played the Jefferson... They used

two treadmills in the chariot race and they had four horses abreast and

revolving scenery in the background... It took more scenery than

any other show that ever came to Birmingham until My Fair Lady."

It is fortunate that over the years several people who actually witnessed

performances at the Jefferson recorded their memories for posterity. In

1960, stage hand Henry Holtam told the Birmingham News about

one of his most vivid recollections: "Ben-Hur

was the most spectacular show that ever played the Jefferson... They used

two treadmills in the chariot race and they had four horses abreast and

revolving scenery in the background... It took more scenery than

any other show that ever came to Birmingham until My Fair Lady."

During

Birmingham's centennial celebration in 1971, an unidentified News

reporter dug out the story of what became of the Majestic in its later

years: "In 1917, the Maddocks-Park Stock Company

took over the Majestic. Originally one of the old traveling shows under

canvas, it presented melodramas. The Maddocks-Park Stock was discontinued

in 1921." The reporter did not go on to tell what happened

after that, but amazingly, the building that housed the Majestic still

stands. For most of the years since the 1920s it has served as a furniture

store of one brand or another, with seemingly no remnant of its days as

a vaudeville theater.

During

Birmingham's centennial celebration in 1971, an unidentified News

reporter dug out the story of what became of the Majestic in its later

years: "In 1917, the Maddocks-Park Stock Company

took over the Majestic. Originally one of the old traveling shows under

canvas, it presented melodramas. The Maddocks-Park Stock was discontinued

in 1921." The reporter did not go on to tell what happened

after that, but amazingly, the building that housed the Majestic still

stands. For most of the years since the 1920s it has served as a furniture

store of one brand or another, with seemingly no remnant of its days as

a vaudeville theater.

After

the arrival of the Lyric, the older vaudeville theaters began closing up

one by one. The repertory company from the Jefferson Theatre transferred

their allegiance to the Lyric, where they became known as the

Favorite

Players. (Look closely at the Eighteenth Street side of the Lyric building

even today, and you will see a fading sign painted on the brick, advertising

this troupe.)

After

the arrival of the Lyric, the older vaudeville theaters began closing up

one by one. The repertory company from the Jefferson Theatre transferred

their allegiance to the Lyric, where they became known as the

Favorite

Players. (Look closely at the Eighteenth Street side of the Lyric building

even today, and you will see a fading sign painted on the brick, advertising

this troupe.)